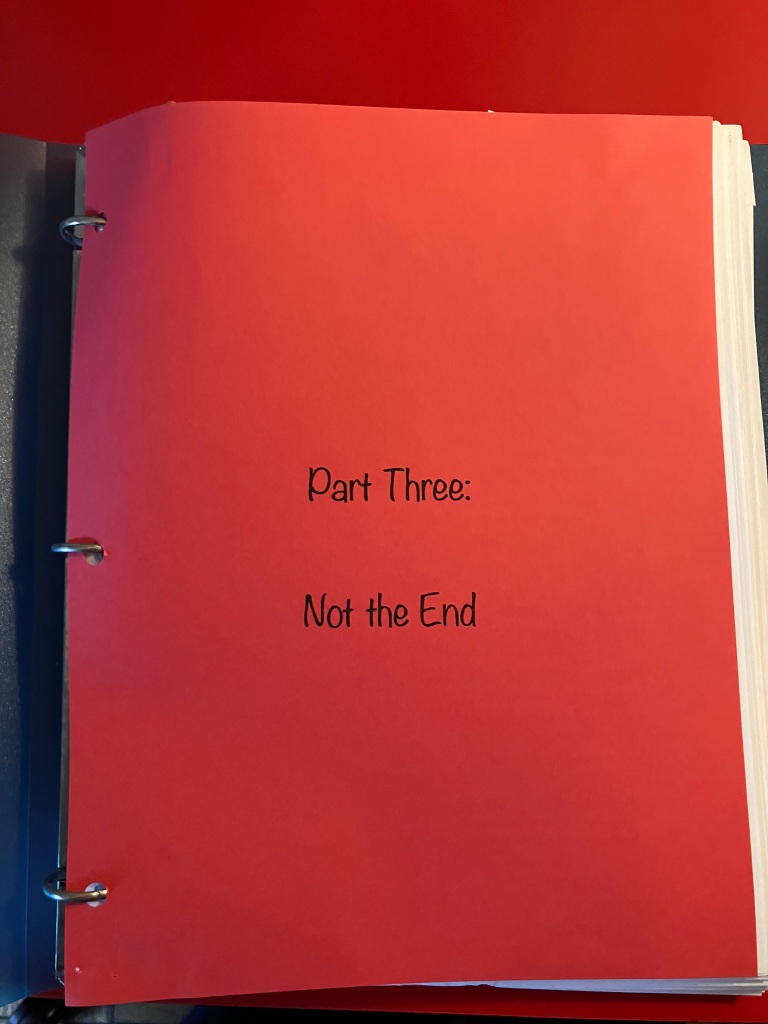

The final essay in this part, and the book, is

"Something to Endure."

Super exciting news: my manuscript is complete, and I will now be entering a new stage of the writing process — the querying-agents phase.

But before I got here, when I was revising and rewriting my manuscript, I had to make a decision regarding my final essay. I had three essays that my book coach and I agreed were all possible candidates for that all-important last essay in the book.

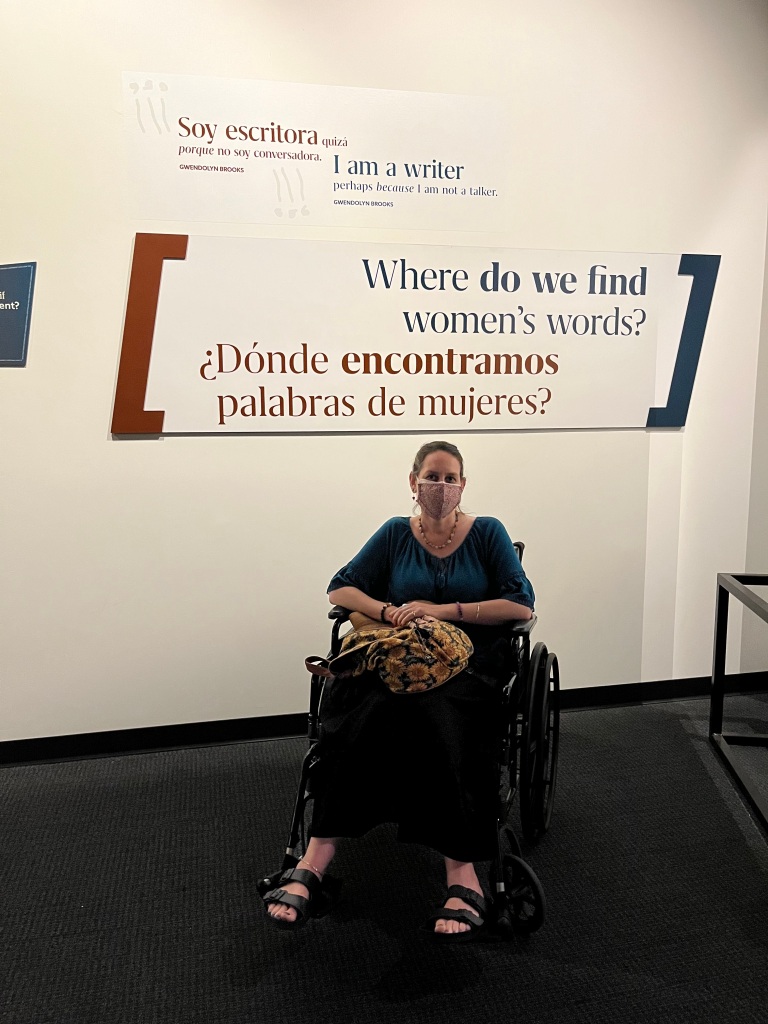

It is my hope that my memoir will be read by those living with chronic illnesses, as well as those who know people who are living with chronic illness. I’m hoping that my story can serve as an example. Though the medical specifics may vary, the emotions may be quite similar. So someone who lives with diabetes, for example, could give my book to a loved one, point to one of my essays, and say, “Here. Read this. This is what I feel like sometimes.”

For far too long, terms such as “disability” and “disabled” have been too narrowly defined. I really want my memoir to broaden those definitions, and I would like my story to serve as just one example of what a disabled life looks like.

When I started working with my book coach, I told her I was writing the book I needed to read when I became ill. I hope after reading my memoir that my chronically ill readers feel less alone and more understood. Along those lines, I want my final essay to give readers a sense of comfort, a dose of good-feels.

Before making my final decision, I stopped to reflect and think about how I want my readers to feel when they’re done reading my memoir-in-essays.

These were the adjectives that I came up with:

Hopeful.

Enlightened.

Inspired.

Comforted.

With that in mind, I made my decision (and my book coach agrees). My final essay is titled “Something to Endure.” Because basically that is the bottom line when it comes to chronic illness. You have to endure the illness. You need to stick it out and figure out ways to handle it, to be with it day-in and day-out for the long haul.

But you don’t have to do it alone. Books, including my own, connect us.